The day my stepfather flew away, I was left with a sheared-off tree. The torn tree stands like a sculpture in my backyard, reminding me of my woodworking father, a carpenter, and our struggle between this life and the next. Earlier in the week I’d gone to San Diego to see my father, knowing his time was near. That night, as he lay dying, a huge storm blew through the Columbia Gorge where we now live.

The night before, we were in Bend, OR where we once lived. A friend had a dinner party to celebrate several occasions. The day my stepfather flew away was my husband’s birthday and our oldest son’s wedding anniversary. That night was also occasion for further celebration– Lily received an award for poetry and I received a short story award from the Central Oregon Writer’s Guild where we were invited to read together, a first for this mother and daughter. Celebrations often bring reflections.

The next morning I got the call and knew my father was gone. Later that day, when we arrived home, the view out our kitchen window revealed a squalid scene of uprooted trees and broken branches. In the forest of our backyard, the bank slopes sharply down to a creek, then rises again on the other side. Across the creek a large oak tree had split in two and fallen toward our house at and angle that just missed our deck. As it fell, it sheared off another tree about twenty feet up its tall trunk. The raw wood of the tree reveals a V-shape at the apex, one side splintered off into a thinly connected wing. Still damp, the exposed core reflects the sunlight as it careens down the trunk, twisting to one side, then shears off at a sharp angle. Red sap oozed around the fresh wound, outlining the design with a red-orange glow in the final rays of the dying day.

The year before, an arborist removed a tree that threatened our house and deck; otherwise we might’ve come home to far more devastation. I gazed out on this scene, in awe of the mess — tree branches broken off with such force they stuck in the bank like sheared saplings; but this tall, ripped-in-half tree appeared as a sculpture, a piece of freshly hewn wood, an ethereal piece of art proclaiming something–a message if I could just see it. A great struggle, a greater victory. It appears abstractly as a diving bird, or descending dove, holy spirit-style. Once you’ve seen it, you cannot unsee it.

How much faith is enough? I’d pondered this question, along with the strength and size of a mustard seed on the day my father flew away, asking for a sign that his spirit lived.

He had gone to church for some of his life–many of my childhood years, and certainly his early years as one of twelve children growing up in the backwoods of Maine. When I was nine, we’d driven from southern California to Maine in his work truck, outfitted with a camper shell, heading to a family reunion in honor of his parent’s 50th wedding anniversary. At the time of his death, he was the last survivor of his six sisters and five brothers.

When I was four, I was the flower girl in my parent’s wedding. They were happy for awhile, but theirs was a tumultuous marriage, not pretty toward the end. They complained loudly about each other, treating each other poorly. He had a sense of humor, an occasional sparkle still frequenting his mischievous eyes, so my sympathies often lay with him. He’d never given me any reason not to love him, and so many reasons to laugh.

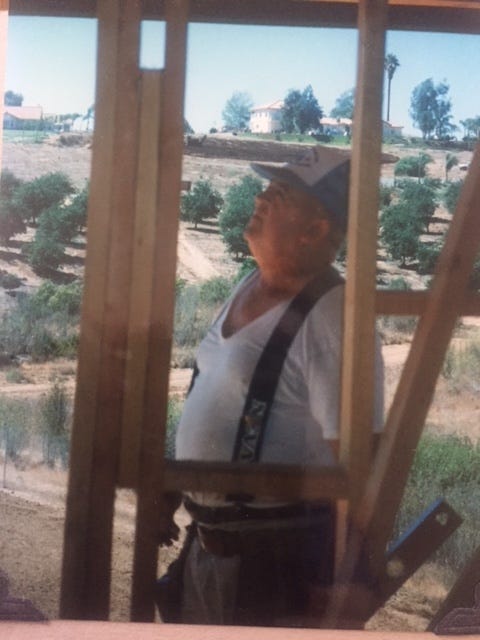

In the year before his death, I’d embarked on an all encompassing project–refinishing the maple cabinets in our new house. I called him often asking for advice. He was a perfectionist with wood. It would take several sandings and several coats of finish, sanding in between, to get the smoothness I’d be happy with, he’d say, sometimes by phone, and sometimes in my mind. When you know someone well, you have conversations with them even when they aren’t there. You ask and the answer comes, in their voice.

When I went down to California the last time to see him, his liver was failing; the doctors suspected cancer. We talked of many things, and then he said he’d been hunting at the club the day before…

I said I thought he’d come to the hospital in an ambulance.

Oh, he said, looking a bit confused. He talked about Maine and how beautiful it was this time of year.

I said I thought heaven would be a lot like Maine, only better.

He got that far away look in his eyes, like he was halfway there, already leaving us. I knew I was saying good-bye then, that we would not be together again in this life, that it was time to let go of my beloved Pa.

As he lay in his hospital bed, I asked him if he’d like to go home. He nodded.

I wish you could go with me, he said, looking me in the eye, but also already half gone.

I had to go back to Portland, to my family, I said.

Those were his last words to me. I wish you could go with me.

He built so many things during my life, including my dream house, and he left me with a love of working with wood, and a respect that runs clean through me. Every time I look out my windows and see My Father’s Tree, I’m reminded not only of him, but of the sign I asked for, the question I posed. Maybe we have not, because we have not asked. I don’t want that to be true in my life, so I ask. It never hurts to ask. And sometimes the answer is immense comfort. When I see this sheared off tree I see a sign and a symbol of both gratitude and loss, the way life is, but it is also an answer, for those with eyes to see.

My mother didn’t allow us to gather to memorialize my stepfather, but the tree is a memorial I see every day. I still talk with him. I still ask my him questions and then wait–the answer comes, as if we’re still talking, because I believe we are.

When I see his tree, I’m reminded of how he loved wood, and how our heavenly father cares for us, enough to give a sign when we least expect it, something made of wood, undeniable.

A tree. A sculpture. A work of heavenly art. And though not exactly outwardly audible, I hear his voice.